Since everything in trinary logic can be represented in binary, why bother with trinary?

Because of a well-hidden aspect of the excluded middle it requires four bits of binary to carry the full value of a single trinary trit.

I never knew this before just now[1]. The thought completed itself as I was ambling through a philosophy.stackexchange discussion, which was one of several browser tabs opened while searching whether Latin embeds binary logic into its grammatical structure. I didn't find what I was looking for[2], but I found something deeper, including an excellent example of how to write this new insight of mine symbolically by borrowing a little bit of symbolism presented in the discussion.

The StackExchange topic is familiar to me. One commenter is asking for "an example of a non-binary relation that cannot be expressed in terms of unary and binary ones." In short, he's asking: what's the point of studying trinary logic since everything in it can be easily reduced to binary? I remember similar conversations years ago with my smart friends who were reacting to my obsession with trinary logic and were arguing against its merits in a similar fashion.

In the same awkward manner as the original commenter on StackExchange (at one point he writes "it is hard for me to articulate my trouble"), I did not have a coherent response back then. I understand now it's because my understanding of trinary logic was embedded with certain binary logical fallacies. Being oriented around my ego -- as fallacies often are -- these fallacies were invisible to me. However, these flaws made my discussions incoherent, which strengthened their position. We always ended with an impasse on this point: everything in trinary logic can be represented in binary, so why bother with trinary?

I've since disentangled my thinking from enough logical fallacies that I can defend my position more coherently. And now I can do it with the precision of symbolism, thanks to today's discovery. Because the point is subtle and new, I want to go through this carefully to make sure I understand it properly. Below, I will quote the discussion from StackExchange, and then add a deeper dive into the new insight. Note that the conversation quoted below has three participants, but two of them are defending the same position. Note also, I skipped some tangents, trimming the quotations to the narrower thread which is relevant to the point I'm making here.

A preliminary summary of the StackExchange discussion

In the following discussion, Kevin Holmes is asking the question and making the same points I was making with my smart friends, coincidentally around the same time (2014). He's right, but isn't able to put it into words with precision (neither was I). BrianO comes in and saves the day, giving a more sophisticated answer. And Hunan Rostomyan represents the binary-logic-centered answer which is the common response to this question. He does this well. His symbolic explanation laid out the elements so carefully that I was finally able to see the omission he's making, which BrianO later addresses.

After the quotes below, we'll dig into the corrected symbolic position. Feel free to skim the quoted conversation for now; it gets tedious, and I'll revisit the important parts with the narrative which follows below.

Here is the conversation from a StackExchange question by Kevin Holmes: "Is there any reason for the heavy focus on binary relations in formal logic?":

Kevin Holmes: Basically, I'm asking if there is any reason why formal logic focuses on binary relations involving one predicate among the vast sea of other kinds of logical relations that also express our concepts?

Hunan Rostomyan: Interesting question. Do you have an example of a non-binary relation that cannot be expressed in terms of unary and binary ones? Between(x,y,z), for example, which is true just in case its second argument is in some sense between its first and third arguments, could be expressed as RightOf(y,x) & LeftOf(y,z).

Kevin Holmes: I think the textbook example is when person x gives gift y to person z. I don't see any way of reducing this to binary relations.

Hunan Rostomyan: We rarely come across treatments of more than binary relations. While I do not know what the reason for that is, I suspect it has something to do with the theoretical dispensability of relations of higher arities. Here's why they're theoretically dispensable.

§2. n-tuples as nested ordered pairs

Since from the set-theoretic point of view, an n-ary relation is just a set of n-tuples, it is possible to reduce an arbitrary n-ary relation to a binary one. We start either by defining the ordered pair (a,b) in terms of sets (by Kuratowski's or Wiener's or some such method) or taking it as a primitive so long as the equivalence [ (a,b) = (c, d) iff a = c and b = d ] holds. Having defined the ordered pair, the 2-tuple, we can then define triples (a, b, c) as the pairs (a, (b, c)), quadruples as the pairs (a, (b, (c, d))), and in general n-tuples (a1, a2, ..., an) as the pairs (a1, (a2, (..., an)). Let's apply this to your example:

The ternary relation GivesGift is the set G = {(x, y, z) : person x gives gift y to person z}, where we have two types DPeople of persons and DGifts of gifts and x, z ∈ DPeople and y ∈ DGifts. For the sake of concreteness let's assume DPeople = {Ruddy, Saul}, and DGifts = {Meaning and Necessity}. We express "Ruddy gives Meaning and Necessity to Saul" as GivesGift(Ruddy, Meaning and Necessity, Saul), which is true just in case (Ruddy, Meaning and Necessity, Saul) ∈ G. By the previous technique, we can represent G as G' = {(x, (y, z)) : person x gives gift y to person z}, and instead give the truth-conditions of that proposition as: true just in case (Ruddy, (Meaning and Necessity, Saul)) ∈ G'. The difference is that G is ternary and G' is binary, but they are functionally identical.

By the same technique, any other n-ary relation can be reduced to a binary one. Needless to say, this doesn't mean that non-binary relations aren't worth classifying and investigating.Kevin Holmes: I have a really hard time with your claim that ternary relations are theoretically dispensable, but it is hard for me to articulate my trouble. I basically think that something has gotten lost in translation. I've been using logical relations as a formal representation of ideas. When I doubt that the giving(x,y,z) relation can be reduced to lower relations, I mean that something is lost if we say that giving(x,y,z) = giver(x) & gift(y) & recipient(z), because the connection between x, y, and z are lost. Similarly, something is lost if you say that giving(x,y,z) = gives-to(x,z) & gift(y).

Hunan Rostomyan: I'm not convinced that what's lost is theoretically significant, since the truth conditions of ternary relations and their binary reductions seem to me plainly to agree. But I do understand your worry.BrianO: Of course if you have a pairing operation then all you need are binary relations. But that's cheating! If the domain of a model consists of people and gifts, then it doesn't contain any pairs of people and gifts: the pair (Meaning and Necessity, Saul) is neither a person nor a gift.

Hunan Rostomyan: My contention is this: (a, b, c) = (a, (b, c)) = ((a, b), c).

BrianO: Note that you can't in general reconstruct a ternary relation from its binary projections (each obtained by dropping a coordinate). Consider your giving relation G(giver, gift, receiver). Suppose John gave Sally (a copy of) "War & Peace". The binary relations tell us that (1) someone gave Sally "War & Peace", (2) John gave Sally something, and (3) John gave someone "War & Peace", and. From (1), (2) and (3) you can't conclude that John gave Sally "War & Peace" — it's consistent with (1)-(3) that, say, John gave Sally candy, John gave Mary "War & Peace", and Dave gave Sally "War & Peace".

From: Is there any reason for the heavy focus on binary relations in formal logic?

A brief analysis of the discussion

The discussion appears to me to be, at essence, a conversation about logical commutativity. Commutation is better known to me in mathematics than logic, but it's a topic I was reading about recently (again[3]), so I recognize it. Hunan's elaborate and precise example of the difference between binary and trinary was a good exercise for my brain because it was while reading that passage that I saw the insight which prompted me to write this present article. His example is complicated on the surface, even though the underlying point is simple. Thankfully, he simplifies later with the following line:

My contention is this: (a, b, c) = (a, (b, c)) = ((a, b), c).

BrianO shows where this fails with the observation that "you can't in general reconstruct a trinary relation from its binary projections". He then gives a more detailed example of his own which shows how there are many ways to misinterpret a binarized triad because something is lost when trinary gets converted to binary. I love this approach.

Including the excluded middle

But I want to talk about something that may go deeper into the problem, solving it at a more fundamental level. It has to do with the flash of insight I saw while reading. I already knew that the excluded middle of any binary relation is a hidden trinary component[4], so today's discovery is this: When you map two binary elements (say, true and false) into a trinary relationship, you have to count the excluded middle TWICE. In other words, each of the binary elements has its own discrete relationship to the excluded middle.

This makes for a total of four logical pieces: 1. a binary element [1+1=2]. 2. its hidden connection to an excluded middle [+1=3]. 3. the other binary element [1+1=2]. 4. its hidden connection to another excluded middle [+1=3]. The two excluded middles are not contiguous, as they are in trinary logic, where middles are included as multiple instances of a single universal middle. As I use it, true trinary logic's included middle represents a single indivisible connection to all things. It can be referenced multiple times, but each of these references have a single referent in common.

This is the important insight which I saw in mind's eye while reading the StackExchange discussion above: The two excluded middles separating the two binarities are not the same thing twice as they would be seen while using trinary logic (multiple references with a single referent), but they are two different things (singular references to multiple referents). When these two separate middles are added to the two polarized ends (true and false), this makes a total of four logical elements.

[Update, several years later: Having studied this comparison more deeply still, I would write that paragraph quite differently now. But I am keeping it as is because this whole article is an important step in the process of learning how all this works as I continue to transition out of an inherited binary mindset into a proper trinary one].

Let's use maps to illustrate what this looks like

Even as I write these words, I'm seeing a deeper insight: Including this universal connection to everything implies there is a single contiguous logical territory which looks and feels like the real world, with mountains, valleys, rivers, lakes -- all represented within the substrate of trinary logic. This ties into a structure that I've written about before:

---------------------Binary map--------------------- ---------------------Trinarymap-------------------- --------------Territory (i.e. "reality")------------

For the first time, I now see something holistically which I recognize from many previous fragmented intuitions: There is no single "binary map" as is being represented in this illustration. The binary map layer should have breaks in it, like this:

------ ------- ------Binary map-- ------- ------- --

In other words, starting from the bottom: Yes, there is a single territory. Yes, there is a single trinary map. But there is no single binary map. The binary map is fragmented into many pieces. Instead of being one contiguous whole, there are many disconnected islands. These discontinuities are what nobody sees. There is an underlying assumption they are connected to each other, but they aren't.

Each of these islands is either a linear line, or a flat plane. They are all flat because each element is equal in status to any other element: if any element were above or below the others, there would be more than a simple binary division. In this way, binary logic flattens everything, making everything equal.

We tend to think of true as an opposite of false -- so how could it be equal, isn't true better than false? -- but note that the opposition is internal to binary logic. And it's an abstraction. From an external perspective, in other words analyzing binary logic from outside of its own way of organizing information, true and false are forced into a single plane, which is quite different from how trinary logic would organize the same information.

The four logical elements

Originally I brought the map idea into focus so the four logical elements could be mapped, but in doing so I stumbled upon the insight about how trinary logic is connected, or as I put it earlier: "there is a single contiguous logical territory which looks and feels like the real world, with mountains, valleys, rivers, lakes -- all represented within the substrate of trinary logic." And then I observed the discontinuities in the binary map, and compared the two forms of logic like comparing two maps of the same territory.

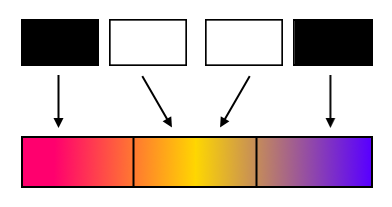

This seems like a detour but in following that tangent, I now see more clearly how the binary map fragments work. In the flash insight which precipitated this article, I saw four "bits" mapped to three "trits," so to speak. The four bits were in twos, like magnets with north and south poles:

This happens because there is no middle between the two whites. The middle, which is another way of saying "the infinity which connects everything to everything" is excluded from the middle, which pushes it to the outside. This effectively forces infinity to exist outside the island.

...

This is probably not making much sense to the ordinary reader, but it's how I'm working my way through the thought experiment which extends from the flash of four elements which came to mind, so let me see how it works out symbolically:

(a, b, c) = ((a, b), (b, c)).

Yup. That's it.

...

Wait...

...

Uh, no that's not it....

...

A proper conclusion to this matter

It's now the end of 2025, more than two years since I started writing this article. I'm reading through this uncut gem to which I have come back many times, trying to complete it. The originating insight long ago slipped away from my mind. I never got far into the editing process while trying to recover it. I always ran out of time, etc.

But today, I've matured enough in the study of true trinary logic to see clearly how to resolve this as originally intended. Actually, a little better, since I've learned a few more things about "context" which I didn't know at the time I was originally writing. I'll touch on that briefly at the end of this article.

Let's go back to BrianO's concluding comment, and look at it in isolation. I still think this sentence is the most important insight: "Note that you can't in general reconstruct a ternary relation from its binary projections," but let's drop in to his example a little more:

BrianO: Note that you can't in general reconstruct a ternary relation from its binary projections (each obtained by dropping a coordinate). Consider your giving relation G(giver, gift, receiver). Suppose John gave Sally (a copy of) "War & Peace". The binary relations tell us that (1) someone gave Sally "War & Peace", (2) John gave Sally something, and (3) John gave someone "War & Peace", and. From (1), (2) and (3) you can't conclude that John gave Sally "War & Peace" — it's consistent with (1)-(3) that, say, John gave Sally candy, John gave Mary "War & Peace", and Dave gave Sally "War & Peace".

He is correct, but his example is more complicated than it needs to be. Hunan's simplification turns out to be an over-simplification. However, it is also a better starting point so let's start there.

Hunan says in his simplified form:

(a, b, c) = (a, (b, c)) = ((a, b), c)

BrianO is pointing out (a,(b,c)) is NOT EQUAL to ((a,b),c). To write BrianO's version with Hunan's concise form, so you can easily compare between the two worlds, look at it like this:

(a, b, c) = (a, (b, c)) OR ((a, b), c)

There are three triads in play here. Let's imagine they are labeled thus:

- (a,b,c)

- (a, (b, c))

- ((a, b), c)

- There is technically a hidden fourth, but we won't get into it here[5].

Hunan says the first three triads/dyads are all equal[6].

But look closely: In the first compression from trinary to binary (#2), b+c is a state that exists only AFTER the gift is given.

In the second compression (#3), a+b means the gift has not been given yet.

This is not a fallacy of hasty bifurcation. These are definitely two very different things.

In other words, a+b means "a has the gift," and b+c means "c has the gift."

Two completely different states which are not at all equal to each other. It gets better: even clarifying this, there's still something missing. The direction of the giving is not clear.

This is what BrianO is getting at. The "giving of the gift" has been left out. All we have is "intending to give" or "received." In fact, in an extremely rigorous interpretation, it is not clear whether a or c has received the gift or given the gift. Has the gift giving even happened yet? Were there other people involved in the gift giving?

We can see immediately that the information lost in compression to binary is not trivial. It's essential to understand what is actually happening.

Alright, so that's the proper conclusion of how to view the StackExchange conversation. Now let's get back to the mapping of four bits to three trits.

The four logical elements (again)

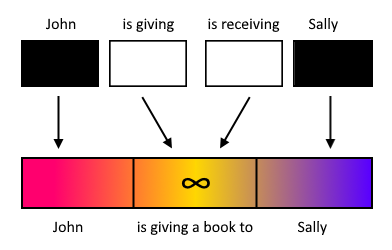

I ended up confusing myself when I tried to map the original illustration above, so I don't expect others to immediately get this either. However, here is (one) correct mapping of the example given by BrianO above:

Consider this a rough draft. The illustration is definitely overloaded. When I made the original illustration (further above in the article), I intended to talk about true/false instead of John, gift, Sally, etc. That aspect should eventually be done, but not here. To keep my illustration somewhat understandable without going into ludicrous technical detail requiring multiple illustrations (yet), this will do for now.

As you consider this, you can see immediately there is a connection to infinity (∞) which comes built-in to trinary logic. This will seem like a leap, but after years of study, I can safely say this is the ONLY correct "hidden assumption" to make when you go about defining a logical system. I have much to say about this elsewhere, but for now, I'll say this:

Beginning with division (which happens when you assume the Law of Excluded Middle as Boole did when he formalized binary logic), you end up creating something which works in a short frame, but in the longer frame, lacks important elements of internal coherence. It might take awhile, but eventually the structure collapses when it encounters anything truly large, such as mathematical infinity. If there is ever anything which is inevitable, it is "everything," which is effectively infinity. Therefore include it at the beginning, as true trinary logic does, and everything works. Whenever you need to reach into infinity and pull out something new, it's right there, with you all along.

To be concise: If you do not include infinity in the beginning, you'll eventually need to admit it later. It can be very unwieldy later in the process, where it might need to be inserted in multiple places simultaneously. Thus, true trinary logic starts with the safe assumption that infinity exists, and with that as a foundation, builds upward.

All this to say: "is giving a book to" at the bottom of the illustration can effectively be anything. BrianO gives the example of "John gave Sally candy, John gave Mary 'War & Peace', and Dave gave Sally 'War & Peace'." Although BrianO doesn't mention infinity, he's talking about an infinite range of possibilities.

Ergo:

Because the Law of Excluded Middle excludes infinity, it oversimplifies.

Context

This access-to-everything of the trinary middle is what I've been calling "context" in my more recent thought experiments. I've written about context from various directions, more and more over the past few years as I've done many thought experiments. All along, I've been seeking what to call this Included Middle when we're not talking about logic or mathematical terms like infinity. I'm now using context all the time, because it is a label which fits almost all use cases.

For a very telling example, Claude Shannon, when he was developing Information Theory, references it, but not as explicitly as I'm doing here. I puzzled over his paper for years and years, trying to find what was the trinary aspect that he was missing. I knew it was there somewhere. Then one day, I saw it.

He talks about binary ones and zeros as if that were all that needed to be communicated, but he also talks about the information needed to decipher the ones and zeros. Not the decryption algorithm. Not the information embedded in ones and zeros, but the context needed to decipher the embedded information.

A piece of decoded information without context is not fully decoded. The word "Rosebud" from the Orson Welles movie is a great example. Without context, it's practically meaningless... or... has too many meanings. But with context, oh my goodness, how much meaning is embedded in that single word!

I'll write more about this true trinary logic intersection with Information Theory in another article some day, but suffice it to say, once you understand the role of the Included Middle, you'll see it everywhere. Hidden in plain sight by not being explicit about ALL assumptions when we build a logic.

Fini

Whew. I've been working on the ideas revealed here for about fifteen years, ever since my smart friends first started constructively critiquing my nascent ideas. The StackExchange conversation which precipitated writing this article was 11 years ago. I stumbled upon it 2 years ago. I finally finished writing this today, which happens to be the last day of 2025.

This article is still a rough draft in that there is a much more rigorous version which remains to be written, perhaps as a chapter in a book. And, this is only one of over a dozen related points to be made in systematically comparing binary and trinary logic. They need to be gathered together so others can understand this terra incognita for the New World that it really is. I've touched on those other dozen points in articles throughout this website, all stored in the "Rough Drafts" folder because I know this is all formative and awkward.

As I write these words, happy to see this major criticism of true trinary logic addressed in a manner that can be understood by anyone, I'm thinking of Kevin's words above: "it is hard for me to articulate my trouble."

Yes. I've known that feeling for a long time. It's haunted me, kept me up at night, made me look foolish, and been a burr under my saddle for years. But no more.

I'll get better at saying it, but I'm soooo glad this element of truly non-dual trinary logic is now in place.

Footnotes

- ^ "Just now" originally refers to late September 2023, but it wasn't until early January 2024 that I realized the most important part of this insight, which is how the excluded middle implies a substratum of division whereas the included middle implies a substratum of unity. While this to the trained eye seems obvious on the surface, in fact these are two very different middles which require very different representation when mapping to binary. This January insight is deeper, and it is one I have sought for years, as it solves many riddles at once.

- ^ Updating this article after I wrote much of it, I have since gone back and tried to research how and where Latin embeds binary logic into its grammatical structure. Although I already feel certain that this is the case (it would be remarkable if it weren't), it's not an easy thing to search for, because there are so many references to "Latin" and "logic" and even "grammar" which have nothing to do with this specific point. There's probably a key word which describes this concept to logic-of-grammar specialists, but after reviewing dozens of pages on ancient logic and finding almost nothing on the logical presumptions of Latin grammar, I've moved on to other topics. Perhaps someone out there can enlighten me? Please do write a comment.

- ^ In the linked example, I was learning about commutativity a few years ago, but frankly none of that awkward episode stayed with me. The more recent discovery -- that Clifford Algebra is fundamentally about non-commutativity -- is finally making sense out of all the references to commutativity over many years. Because of the reputation of Clifford Algebra (that it maps onto physics more elegantly than "normal" algebra), I am now beginning to realize reality is non-commutative. This seems to be a rather deep insight, but I do not know yet what it means.

- ^ "The excluded middle of any binary relation is a hidden trinary component" is an insight I've written about in previous weblog articles. When seen from normal binary logic, the excluded middle is quietly assumed to be true and thus it is not included as a visible third component of the true/false dichotomy. However, when seen from within trinary logic, the excluded middle's role is explicitly included as a first class element along with true and false. It is not hidden, it is explicit. On the surface, trinary seems to require more elements (as a triad is "larger" than a dyad), but in fact, the two forms of logic both require three elements. Thus binary logic is simply an implementation of trinary logic with a hidden third pole.

- ^ In full truth, there is even a tiny moment in time when a is giving b to c, where BOTH a and c have ownership of b OR NEITHER a NOR c have ownership. Who owns b in that measureably infinitesimal moment? I propose, in that moment, "the entire universe" owns b. BrianO injects "Mary" and "Dave" into this infinitesimal step, but it really could be anything! However, as interesting as this infinitesimal point is, we're going into too fine a detail for the larger discussion, so we'll leave this as a footnote for the ones who ponder such things and carry on.

- ^ He leaves out #4 because it is nowhere on the map for him. Literally inconceivable within his system.